Taskfile - your app builder helper

Taskfile - installation and use

Sometimes, working on different projects, we happen to use different technologies. Flutter, React, Python or Java have different build systems, each with its own approach to the problem. So what to do, if we want to make sure that even after a long rest from the technology we will be able to quickly build and test our project.

1. Why Taskfile?

The frameworks or languages described earlier have really great ways to build applications. Mostly it comes down to using a more or less complicated client that allows you to build, test and even deploy your project to the cloud. I mean, it’s no problem at all to learn a build system, and that’s what I did for a long time. However, it would be nice to have some unified way to open and manage packages.

Perhaps a single README.md is enough

My first approach to dealing with managing different projects was to write a specially

prepared REAMDE.md file. Despite documenting how we open or test a project, this approach

has several fundamental shortcomings. Let’s face it, who wants to go through the steps of the manual, reading which

of the commands you need to execute to get the project up and running, and get frustrated copying more commands into the terminal to read

later that they weren’t needed in your case. Or who wants to risk taking longer than necessary to prepare the project, downloading more

dependencies.

Ultimately, documenting code and projects is essential, and I myself can’t imagine a professional program without documenting it with an appropriate file. Especially since it looks cool in the project on the Github platform, for example. In any case, I believe, that good documentation is the one written in code. For this reason, more complicated operations I prefer to write in the form of single - strictly defined commands that can be easily called.

How about a bash script?

What if the commands were written in a bash script? Theoretically, it can be done, but here a few problems arise. While shell scripts are designed to automate shell commands, their versatility here is both an advantage and a disadvantage. To use them in the context of building an application, you have to go to some trouble. It is true that you can create loops to process more commands, but unfortunately this requires an awful lot of additional code that obscures the meaning of what you want to achieve. Adding an additional command to the list the available commands, or writing a simple helpa, is additional code complexity that is really not needed at this point.

Imagine at this point still handling some dependencies. Nightmare!!! Admittedly, you can save yourself with some template, but in my opinion this is a game not worth the candle. Especially since such a solution does not look elegant at all.

Makefile? - Sounds great! The

With the requirements described, Makefile seems ideal. We can quickly define what commands to execute,

and then call everything with one simple command.

make install

This simplicity is why I have used this method in various projects. Admittedly, the tool, designed for languages such as c/c++, works well mainly in defining how individual files should be compiled, but as a wrapper for other build systems also works well.

…

I, however, was looking for something better that would help me manage multiple projects in different languages, while providing dependencies between tasks. It should also be easy to use, and customizable enough to not execute the same code and library preparation commands repeatedly if it’s not needed.

Well, and I was annoyed by the strange syntax with tabs, which was a problem on different editors. It was enough to open the file in the wrong editor and already instead of a tab, there were spaces that interfered with the execution of the script. 🤷

So what we gonna do?

And this is where it comes in, all in white - Taskfile.

Taskfile is a command management software written in go language, which is intended to be simple to use.

It is compiled into just one binary file, so that we don’t need to download a million dependencies from the Internet,

which are of no use to us anyway, but only litter the computer. This also makes it easier to implement

this solution in all kinds of CICD systems.

This solution supports not only the simple execution of single commands, but also allows us to define dependencies between them, or execution conditions. For example, we can create a command to download external resources from the Internet, and then add them as a dependency to the build command. Having the right condition for the first instruction, we can also make it execute only if needed, so downloading images or other things does not have to be done every time.

Besides, we also have support for including Taskfile files from other locations. This makes it possible not only to build

structures for multi-package projects, but also to separate instructions, e.g. for handling docker, in separate files.

Suffice it to say that I am able to handle many things using only Taskfile, in which, in addition, each of the

commands can have its own description.

2. Quick introduction

Let’s say we give Taskfile a chance. So how to go about it, so as not to waste your time

Installation - so it’s time to start the fun {#installation}.

Task is a tool written in go language, so that having the appropriate software installed, we are able to install the tool directly from sources. It is also possible to install using one of the package managers for many different languages.

Having Python installed, it is also possible to use a package manager suitable for that language - pip.

pip install go-task-bin

Users of javascript can try the installation using npm

npm install -g @go-task/cli

However, using Linux myself, I prefer to use the snap package.

sudo snap install task --classic

There are also many other alternative methods of installing this software for both Linux, Windows, and even macOS users. They are all described on author’s site.

Simple example

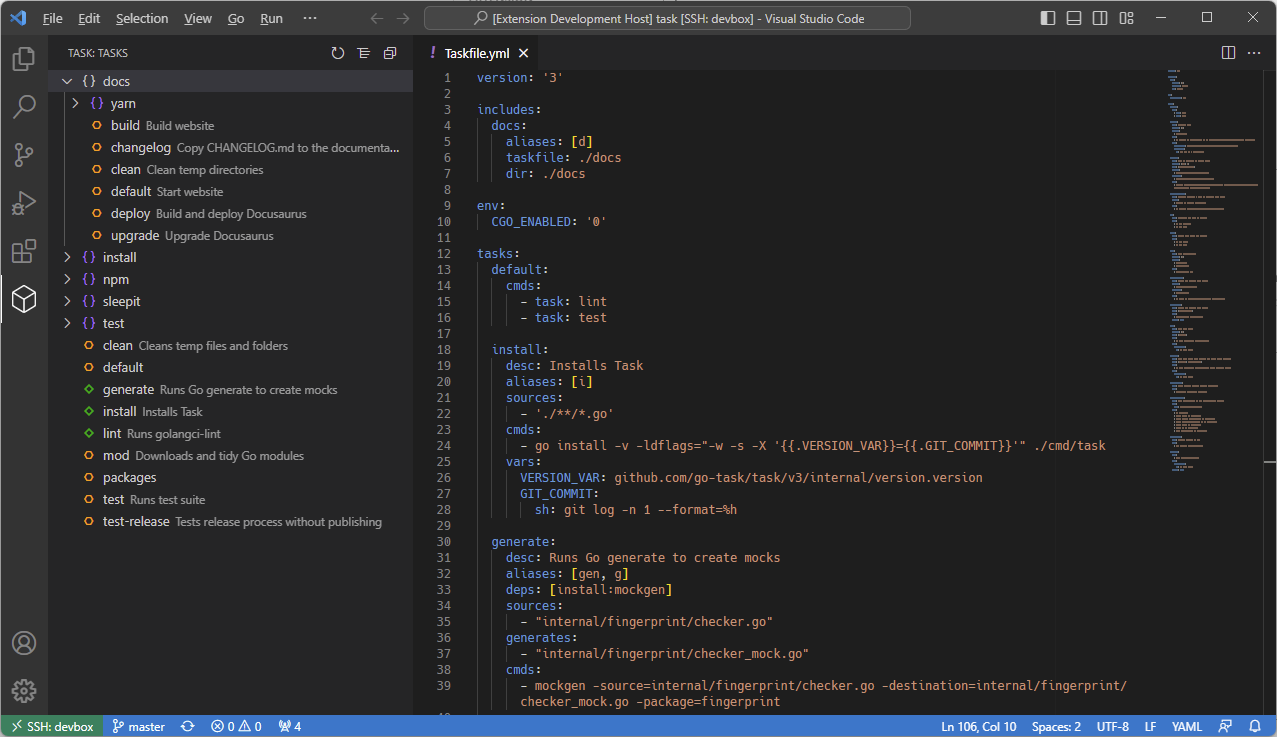

To start using our build system, create a yaml file called Taskfile.yml. If you are working on a

external project, you can add it as ignored in the version control system (e.g. by adding an entry

to the .git/info/exclude file). In private projects, where you want to zacommit it, I recommend adding a file named:

Taskfile.dist.yml, and adding Taskfile.yml to .gitignore so that each developer can annotate their own implementation in their own

if they wish.

The simplest file might look something like this

---

version: 3

tasks:

hello-world:

cmds:

- echo "Hello world"The basic unit of operation in this case is one task. It is the one that describes what the task to be executed should look like. In this case, we created a task called hello-world. Running it, it looks as follows:

task hello-world

The command should print the text Hello world on the screen. By adding new items to the tasks key, we can extend our

file with more commands. More on the yarn manager example.

3. How I use it?

In this section, a few words on how I use this software for my needs.

Working with other package managers using the example of yarn

I usually start working on projects by defining basic commands, which provide a framework for further work. They are common between my projects and allow me to quickly find my way between projects. These are:

- init - Prepares the environment, downloads dependencies, installs missing components. Most often it is a dependency for the rest of the tasks

- start - Starts the development environment

- test - Starts unittests, linters and other code testing tools

- build - Creates a software package ready for distribution

- deploy - This task is usually optional and has the task of sending the built package to the server or to the store

This set is most often extended with additional tasks, which then are usually part of the above mentioned ones.

So let’s use an example, which I will discuss later in the post. Of course, we have to assume that the yarn program has several defined commands such as start, build, test and lint. Let’s assume that they are correctly configured commands and that they do the job their name indicates.

---

version: 3

tasks:

default:

cmds:

- task: start

init:

run: once

cmd: yarn install

sources:

- package.json

generates:

- node_modules/.yarn-state.yml

start:

deps: [build]

cmd: yarn start

test-lint:

deps: [init]

cmd: yarn lint

test-unittests:

deps: [init]

cmd: yarn test

test:

cmds:

- task: test-lint

- task: test-unittests

build:

deps: [init]

cmd: yarn buildheader and default

Let’s start with the first two lines. The first is an optional element in the yaml file that specifies what should be in it.

The next line version: 3 specifies which version of the Taskfil api we will be using. Of course, version 3 is, for this

moment, the current one, and this should be adopted as the default header in new configurations.

We can see that the individual tasks, are grouped under the tasks key. In addition to the tasks I described earlier,

I have also added a task named default in the file. This is a standard key that specifies the task to be executed in case,

if we call the task program without specifying any tasks.

init

This task is in some ways unique in this file. It is supposed to run the tasks of downloading dependencies and general preparing the code to run. It will be a dependency for the other tasks, so it should be executed only once, and only if the code is not prepared to run the other tasks.

The equivalent of init in yarn is the yarn install command. It performs the download of external dependencies for the operation of

build system. It is worth mentioning here that in the scripts defined in yarn, you can not force the option to install

environment, before calling for example: unittests.

In Taskfile, in addition to adding dependencies, we also have the option to add the initial conditions under which this task should execute.

We achieve this with the status key, where we define a command that determines whether the task can be skipped.

In our case, we use the second way using the sources and generates keys. The first one determines

which files are used to execute the shuffle, and the second one determines what will be its result. If any of the files in sources changes, or

does not exist generates we must execute the command. Otherwise it will be skipped. You can

read more about this mechanism here.

The second interesting mechanism in this shuffle is run: once. It is useful if for some reason init would appear

several times in the dependencies, and we want to execute them only once.

More here.

start and build

Here there is no philosophy. Simple tasks with a dependency to init. Of course, when calling both of these tasks we will

try to automatically configure the environment, if needed.

test, test-lint and test-unittests

In this case, I split the tests into two commands test-lint and test-unittests. They can be executed separately or

with a single task test command. Writing the task calls in this way, differs from using the deps key in that,

, when using dependency, the tasks are always called first and we don’t really have control over their order.

It is worth noting here that when calling both test-* commands, we are dealing with a double definition of the init dependency.

By adding run: once there, we don’t have to worry about this command being called twice.

Configure github action

Having the Taskfile configured this way, it is worth using it in automatic testing. For github Aciton, the author recommends

to use the following command source:

- name: Install Task

uses: arduino/setup-task@v2

with:

version: 3.x

repo-token: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}I, on the other hand, use something like this in my projects:

- name: Install Taskfile

run: |

echo "::group::Install Taskfile"

sudo sh -c "$(curl --location 'https://taskfile.dev/install.sh')" -- -d -b /usr/bin/

sudo chmod +x /usr/bin/task

echo "::endgroup::"4. Some other functionalities

The above description captures the nature of how Taskfile works, but does not exhaust all the functionalities. About them, you can read in documentation. However, some of the more interesting ones are worth mentioning:

- ☑️ Using .env files

- ☑️ Using external task files

- ☑️ Command aliases

- ☑️ Parameters in task name

- ☑️ Cleaning up after a task

- ☑️ Describing Tasks (Documentation)

- ☑️ and, of course, many other…

5. Summary

Projects written in different frameworks involve multiple build systems that work differently. Sometimes it is difficult to remember what command to call to build or test an application. In this case, I think it is worth using an easy-to-use wrapper to get the application up and running quickly.

I think a good example, of such a wrapper is just Taskfile. It is easy to use, quick to learn and has really

a lot of capabilities that can be used when needed. It also allows you to take advantage of functionality that

does not have natively in other solutions.

And do you also know of any tools that solve this problem? Write in the comments.

6. Bibliography

- https://taskfile.dev/ - Taskfile project homepage

- https://github.com/go-task/task - Project sources

- https://rafyco.pl/tags/taskfile - All articles about taskfile on this site